During Lent, I gave up checking my phone every morning before work. It was an effort to keep my mind free from the noise of the world: the panicked news alerts, the constant emails, the friendly texts, and a Star Wars game I am far too invested in.

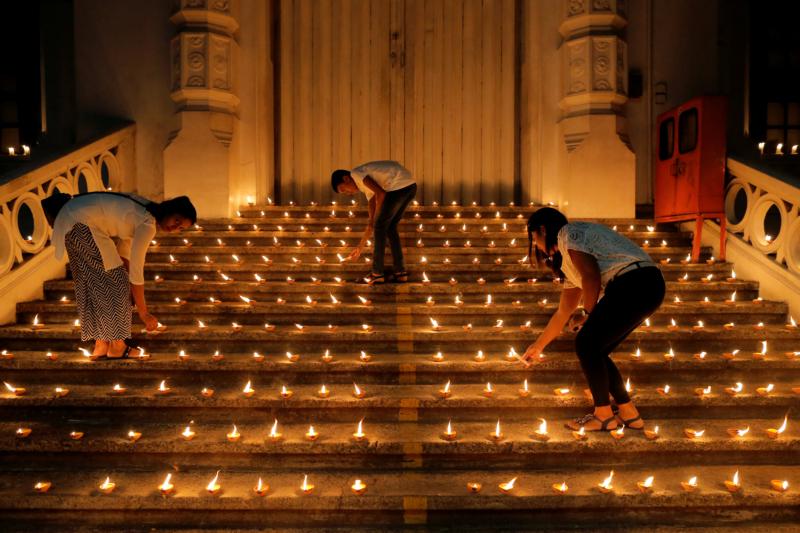

But on Easter morning, like so many of us, I rolled over, grabbed my phone and was immediately inundated with a feeling of sorrow and helplessness. So many lives violently and senselessly lost after eight bombs had gone off in churches and hotels in Sri Lanka.

As I laid there quietly — my wife asleep next to me, my daughter in the next room — it was hard not to think of those families on the other side of the world. Here, on a day meant to point to hope, the news thrust us into despair.

I quickly pulled up my email to check on my Sri Lankan colleagues, fellow Catholic Relief Services employees working to resettle refugees in Sri Lanka. I spent a good part of the morning working with my team to share what updates we could on social media: a note that our staff was safe and a prayer for those partners and friends who weren’t.

RELATED: 3 Things to Do When You’re Feeling Overwhelmed

It’s nothing novel to say this: Following the news these days is to embark on a constant journey of anxiety, fear, and mudslinging. In fact, as disasters occur and rhetoric divides, it’s good practice to take a quick personal pulse: Have I grown too numb to it all? Do I still feel in response to pain, suffering, and death?

For me, on Easter morning, the answer was yes. Yes — I was utterly heartbroken by the news, and I wanted to do something. So often, though, there is so little that I can do. These disasters take place in another community, another state, or another country entirely. I haven’t the skills or the knowledge or the time to provide any meaningful aid. I furrow my brow and purse my lips together, shaking my head. What more can I really do?

Rather than hang our heads in despair, these moments present us with opportunity, a point on our journey where the path splits. Do we attempt to rise to the challenge, using our seemingly tiny voice to speak a word of truth or comfort amidst the cacophony of noise and despair? Do we attempt a small act of resistance, or do we throw up our hands, helpless?

My wife is a mental health therapist working with unaccompanied minors. She brings home stories from these young men — boys, really — that make the headlines of the day sound like synopses of Disney movies. Siblings kidnapped. Separation at the border. Substance abuse.

I simply sit and absorb her words, my eyes wide and my head still. She needs to share these stories or else I can only imagine she’ll explode. And so I listen, my small part to play. And I know that my presence, just across the dinner table, provides her with some bit of courage, some touchstone of comfort.

It’s not my place to help these children; I’m not the one with the skills or experience. But by accompanying the person who can help — namely, my wife — I am doing something for those boys. And my wife is able to recharge, finding herself in a safe space where she has a sounding board.

Violence, terrorism, family separation — these issues are overwhelming. It can be hard for my middle-class mind to make any sense of them, to impose any order. There’s a symmetry that I desire: a problem demands a solution; a problem I perceive demands a solution of me.

That’s simply not how the world works. But we shouldn’t blame our inability to prevent bad things from happening as an excuse to give in to feelings of helplessness. This example and countless others — a school shooting, the opioid epidemic, a changing climate — are opportunities to assess the role we play in a rather large and imposing world.

And after I look around, I can be honest about what I can and can’t do in the face of disaster. Then, I can take action. I can make a phone call to comfort a friend. I can listen to someone in need. I can share stories on social media that is positive, affirming, and true. I can donate money to a charity working on the front lines. Or I can volunteer my time to be present to those who are suffering.

For me, terror in Sri Lanka meant a simple yet important post on Facebook that communicated that our staff was safe (all the more significant in the wake of that country’s total shutdown of social media). For me, gang violence in Central America demands that I be present to my wife as she processes the stories of countless young people. I accompany her so that she can accompany them — and help them on but a single step in their journey.

These are small actions, yes. And these are large, spanning problems. But we’re not all called to be Avengers, Jedi, or Planeteers. But listeners, truth-tellers, sharers of information, shoulders to lean on — those are things we can and should be.

Those are the small actions of Easter hope that banish despair.

Originally published on May 30, 2019.